When you think of coffee farms your mind probably drifts to mist‑shrouded hillsides in Colombia or Ethiopia, not to a valley north of Barcelona. For centuries the world’s coffee belt – the zone spanning roughly 25° N–30° S – has provided the warm temperatures, humidity and rainy/dry cycles that coffee needs. Climate change is destabilising those traditional growing zones; equatorial regions are getting hotter and drier, pests and diseases are spreading and scientists warn that up to half of today’s usable coffee farmland could disappear by 2050. This twin reality – of a shrinking coffee belt and a warming world – is the backdrop for a remarkable project in Catalonia.

From tropical dream to continental reality

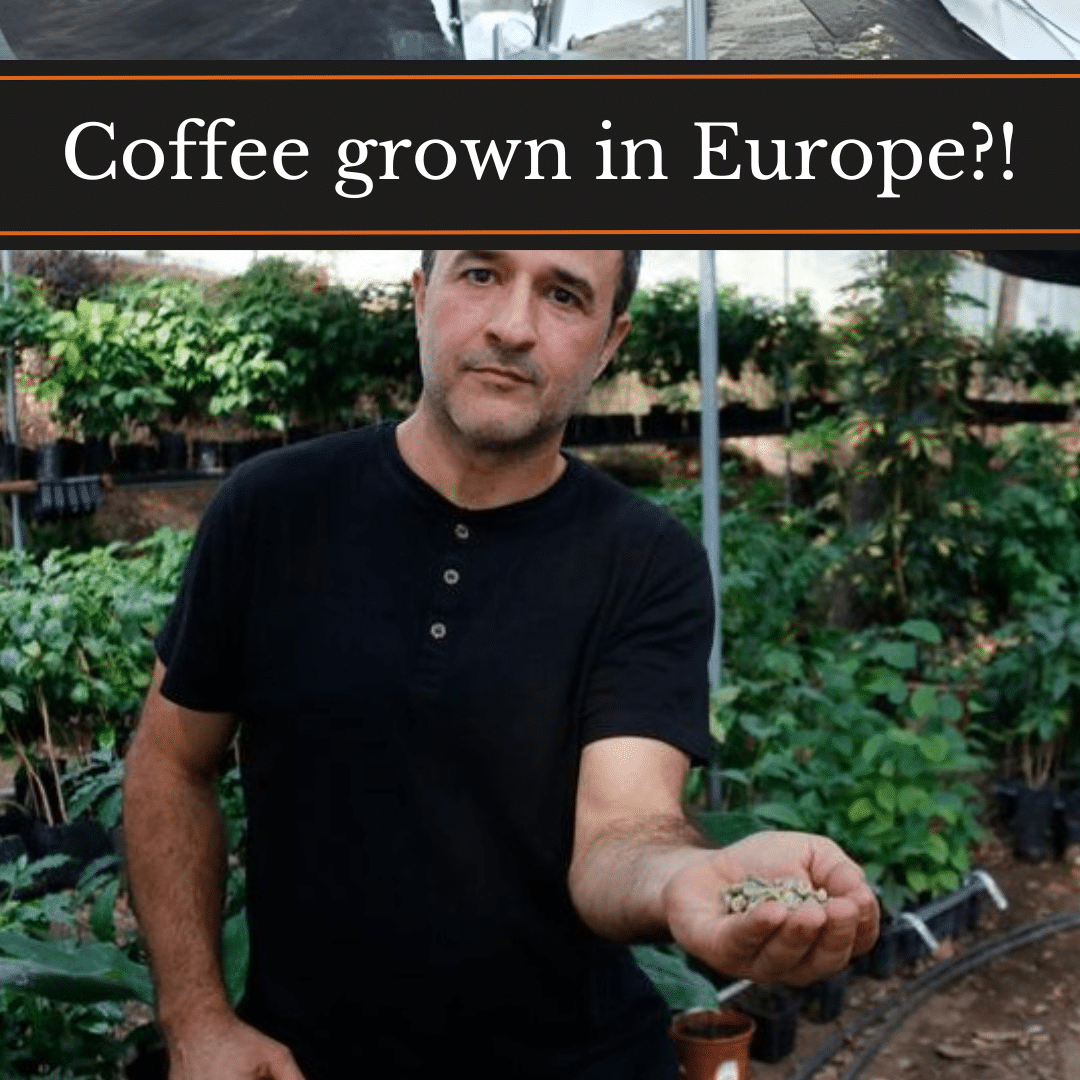

In 2016, coffee experts Joan Giráldez and Eva Prat bought a small farm in Sant Vicenç de Torelló, a village in the Osona region of Catalonia. Their goal was audacious: grow high‑quality arabica coffee in a continental European climate. Coffee plants usually thrive in tropical or subtropical regions; apart from some subtropical estates in Spain’s Canary Islands and in Granada, there was no record of a coffee plantation in a true continental climate.

Giráldez and Prat spent two years studying their plot’s soil pH, historical temperatures and rainfall, eventually choosing a valley site that moderates the region’s wild temperature swings. Whereas seeds in the tropics germinate in about three months, the Catalonian seeds took eight months to a year; only the best seedlings (descended from award‑winning coffee varieties) were kept. They now have around 300 coffee plants on the farm and another 5000 seedlings waiting to be planted.

Joan and Eva holding a coffee plant. / Lourdes Casademont

Adapting to extremes

Coffee plants in Sant Vicenç experience conditions unknown to their tropical cousins. Winter temperatures can drop to -5°C and summer highs can reach 35°C. Frosts and heavy rains are constant risks; Giráldez and Prat live on the farm with their children because “any inconvenience can affect the health of the plants”. To help the bushes cope, they germinated the seeds locally so the plants could “remember” the climate and built partially covered structures that shield the plants from the harshest conditions while leaving them exposed for most of the year.

These stresses slow down the ripening process, much as high altitude does in Ethiopia or Colombia. Giráldez believes the beans will develop more complexity because they take longer to mature; he equates the resulting coffee to a high‑altitude arabica and aims to produce a “unique gourmet coffee”.

The first tiny harvest in 2024 yielded only 150g of green coffee – barely enough for a tasting flight at your local café. If you’ve ever tried germinating an avocado pit on your windowsill, you’ll sympathise: these plants take patience. Joan and Eva have successfully grown the seeds and completed two germination cycles, with the plants now growing to a height of 1.2m. Full production from the existing 300 plants has begun as of mid‑2025, and the farm’s first commercial beans will be offered once the team is confident in the flavour. “We still don’t know how they will develop, what the aroma, flavor, body and other characteristics will be,” Joan explains.

“This will be the first coffee in the world to be grown in a continental climate. We don’t know of any other coffee grown in this climate,” says Giráldez.

Sustainable by design

Giráldez and Prat have built ecosystem resilience into their project. Beyond coffee, the farm includes a large blueberry plantation and a herd of white goats of Rasquera, a Catalan breed that helps control undergrowth and fertilise the soil. Think of the goats as the world’s fluffiest gardeners. This diversification supports biodiversity and reduces reliance on synthetic inputs. Their priority is not volume but quality and education; they want to “raise awareness of the effort that goes into every cup of coffee” and demonstrate that Europeans can cultivate coffee without clearing tropical forests.

Why it matters for coffee lovers

Projects like Castellvilar signal that a warming climate could shift coffee production into new regions. Coffee enthusiasts have long understood that the “coffee belt” may migrate as temperatures rise. Yet this is not a cause for celebration. Climate change is simultaneously shrinking suitable land in traditional coffee countries – scientists predict up to 50% of current coffee land could become unsuitable by 2050 – and reducing yields and quality through heat stress, erratic rainfall and pest outbreaks. Prices are already rising: robusta coffee prices nearly doubled after drought in Vietnam.

Giráldez and Prat’s success does not spell the end of coffee farming in Vietnam or Colombia; rather, it underscores the urgency of adapting and diversifying. By breeding climate‑resilient varieties, improving shade‑grown agroforestry and supporting small farmers, the industry can mitigate the worst impacts. Meanwhile, experiments in Catalonia, the Canary Islands and Granada provide valuable lessons in how coffee might be grown in Europe, all without relying on deforestation. That gets a big thumbs up from us.

A taste of the future

For UK coffee drinkers, Castellvilar’s story is both inspiring and sobering. It hints at the possibility that artisan Spanish coffees may one day sit alongside Ethiopian Yirgacheffe on our shelves, offering flavours shaped by Mediterranean winters and long ripening seasons. The thought of sipping a European‑grown espresso is thrilling, but don’t rush out and replace your hydrangeas with coffee bushes just yet…

At the same time, it reminds us that the best thing we can do for coffee’s future is to address climate change. At Iron & Fire we champion growers who value sustainability and quality. We will be watching the Catalonian harvests with keen interest, and who knows, one day, we may even roast and share this pioneering coffee with our customers. Until then, let’s keep enjoying our coffee whilst supporting the farmers, researchers and innovators working to ensure coffee’s survival from Catalonia to Colombia.

Whilst you’re waiting to try coffee from Catalonia, we’ve got plenty of coffees you can drink right now…

-

Colombian Jazz Speciality Blend

Chocolate, Caramel, Cherry From £7.60 Inc VAT - save 10% with subscription SELECT OPTIONS -

Brazilian Samba Speciality Blend

Rich, Chocolate, Hazelnut From £7.60 Inc VAT - save 10% with subscription SELECT OPTIONS -

Roaster’s Choice Speciality Coffee

From £8.69 Inc VAT - save 10% with subscription SELECT OPTIONS -

House Blend Speciality Coffee

Full Bodied, Chocolate, Nut, Caramel From £7.60 Inc VAT - save 10% with subscription SELECT OPTIONS